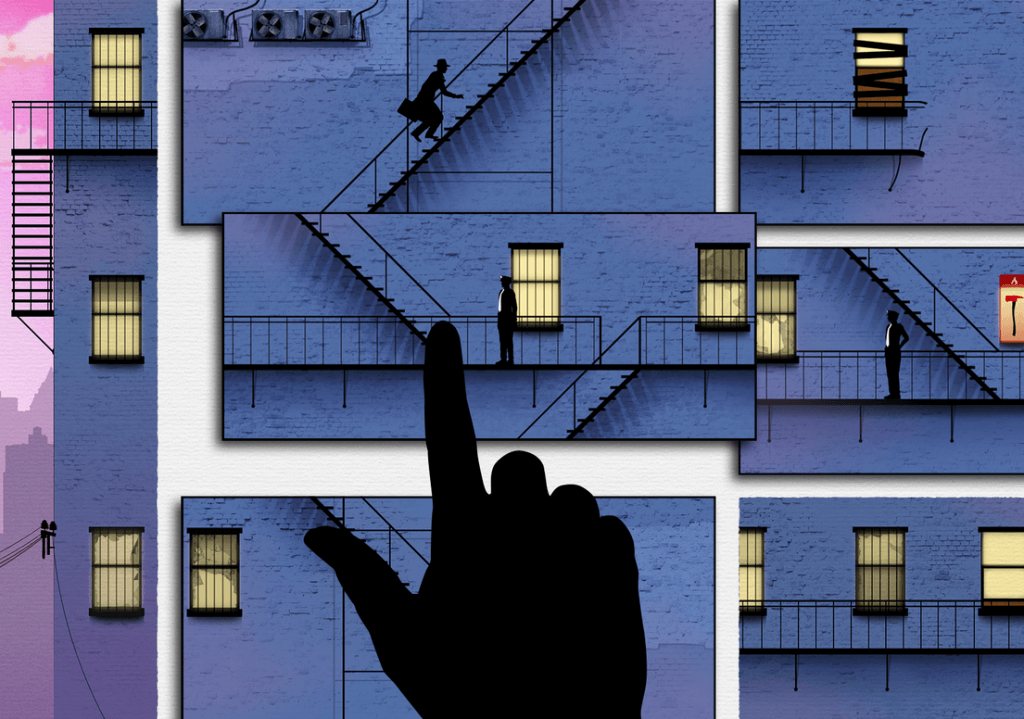

Ollie Browne is no stranger to following his dreams. As a professional musician turned video games artist, he is one of the co-founders of development studio, Loveshack Entertainment, and the lead artist behind hit indie game, Framed.

Since its release, the interactive panel-swapper has racked up an impressive litany of awards including Best Upcoming Title at the 2014 International Mobile Gaming Awards and Best Puzzle Game at Intel’s Level Up.

Ollie talks to us about how a ‘back-up’ career as a QA tester for games turned into a full-time stint as a games artist, and eventually led him to co-found Loveshack with two of his mates.

When did you start taking an interest in video games and drawing?

I’ve always played games, pretty much since the Apple IIe came out. From there I graduated to NES, right through SNES and Genesis to Playstation and onwards. I always just loved video game art and the intricacies of the levels in some of those older, side-scrolling games. The fact that you could alter it and ‘move around in it’, looking at all the scenery, it was just really inspiring to me as a boy. When I was a little boy I was obsessed with Star Wars and used to draw lots of kind of ‘side-on’ drawings of Rebel bases with tunnels and bunkers and secret passageways. I used to draw these for hours. I guess on reflection they were a lot like levels in a game. Of course, I lost interest in games as I got older and they became more of a rainy day hobby than an obsession, but I’ve always been interested in them.

Have been formally trained in art or game design?

After high school I went to RMIT to do a radio production course (due to my interest in rock music again), but found it wasn’t really for me. After a year there, I changed course and started a degree in Fine Arts at the Victorian College of the Arts, specialising in Printmaking. Around this time I started my own bands and was playing music a lot, so once again, the art studies were a kind of background to that.

One of my bands kind of took off after a while, so I finished my degree, but then just played music pretty much solely for a long time. I was on and off touring quite a bit, and a good friend scored me a job doing QA (games testing) at Atari. So I was playing music at night and testing games by day. Around this time I decided that I should have a ‘back-up plan’, so I also completed an Advanced Diploma of Multimedia at RMIT. I continued doing QA for games, too, which led to my first design role at Firemint.

When I moved from QA into design, it was simply because I wasn’t playing as much music and flying all over the place playing gigs and I needed a ‘real job’. There’s a lot of problem solving and creative thinking in games design so it fulfilled my creative impulses as well as being a bit silly and playful, like rock music.

When did you seriously consider becoming a game artist and designer?

I was actually going for a job in QA and they said, ‘Hey actually, we need a designer. Want to apply for that instead?’ So it was when the reality of a full-time job designing games was presented to me that I decided it was a really good opportunity. I also realised that the gaming industry was growing so much as an entertainment medium, maturing in many ways, and that it was becoming something of equal artistic merit to fine arts and music. That sounds a bit snobby, but it’s not meant like that, it’s just that Mario Brothers and Matisse aren’t all that different at the core of it, just great examples of artistic expression, and sometimes games get unfairly seen as juvenile or childish.

How did you come to form your own indie games studio?

Joshua Boggs, Adrian Moore and myself all met working at Firemint. That studio was eventually purchased by EA and Josh and I moved over to work there for a year or two. But prior to that we’d all worked together as the core team on one of Firemint’s final games as an independent studio. That game, ‘SPY mouse’, was a pretty big success, and we felt really proud that what we’d created (along with a really great team of ten or so) was so well received. But it ultimately wasn’t the kind of game we really wanted to work on. Josh approached Adrian and I with the idea to go independent and form Loveshack. It was a nerve-wracking decision, but ultimately the right one.

We prototyped Framed from Joshua’s initial idea (a ‘comic book game’ where you alter panels of contextual content to alter the narrative they provide). We started entering the prototype into game competitions and showing it at gaming events like PAX, and the response was amazing. Soon we started winning awards for it (the early highlight being ‘Excellence in Design’ at the 2013 Independent Gaming Festival awards in China) and getting attention in the global gaming press. So that was the first real hint of success, from there we just had to make the rest of the game, which was the hardest part!

What was it like transitioning to your new career as co-founder of an indie game studio?

From playing music for a living to designing games for a living was a pretty big change. Being a touring musician was really fun, but also very itinerant and draining. So it was a pretty massive change from playing gigs every night in Europe to sitting in front of my computer with Photoshop open. But because I’d been working in games as a ‘side-career’ for so long it didn’t feel unfamiliar at all, and I’d luckily made a lot of friends in the industry, so it was relatively easy for me to get full-time work and transition into it. I feel really lucky because the gaming industry is notoriously hard to get a start in.

It certainly changed my view on games as a hobby. I can no longer simply play them for fun and I’m much more critical than I was in the past. That said, I do still enjoy them, though these days it’s the ones that shake things up a bit and try something new that get my attention. Luckily the industry has broadened so much there’s always something interesting to play that isn’t Call of Duty or Assassin’s Creed (no disrespect to those, though).

What’s been the biggest challenge?

I guess breaking into any industry requires a lot of tenacity and commitment. When I started working in games in QA, contracts often got cut short if games were cancelled or came to the end of development, so I was often instantly out of work. So I had to constantly contact all of the Melbourne-based studios to see if they needed any QA team members. Basically just maintain my network so that I would hopefully be first in line for work. After a while though, if you work hard, you build up a reputation and things get easier.

I guess breaking into any industry requires a lot of tenacity and commitment. When I started working in games in QA, contracts often got cut short if games were cancelled or came to the end of development, so I was often instantly out of work. So I had to constantly contact all of the Melbourne-based studios to see if they needed any QA team members. Basically just maintain my network so that I would hopefully be first in line for work. After a while though, if you work hard, you build up a reputation and things get easier.

The other thing is that the games industry is so multi-disciplinary that you need to be prepared to learn all the time. Not only does it move really fast technologically, as a designer you have to understand what everyone else’s job involves so that you design things that are achievable, not just pipe dreams. You have to understand the limitations the artists, coders, sound people, the writers all have, and work within those borders to come up with something that seemingly transcends them. So you’re always learning, which is great, but sometimes it can be a lot to take in.

What’s the key ingredient to your success?

When I started in a design position I was pretty nervous. Game design is not something I actually studied, so it’s not like I had any ‘experience’ beyond QA (which is one of the best places to start, for any aspiring game designers). I’d never used a level editor before (basically a 2D or 3D program that allows you to build and populate a game area with gameplay elements). But those kinds of things are relatively easy to learn, and game design is mostly about having a broad knowledge base across all mediums; music, film, art, literature (as well as other types of games like board games and roleplaying games). These are the types of things you rely on as a designer, seeing what creative solutions other artists have come up with.

So I think the key thing for me was just trying to find inspiration in things other than just ‘other video games’. Inspiration is everywhere, and while an education in the field, or starting at the ‘bottom’ in QA like I did (not to underestimate in any way the value of QA) are important, and it’s what you do with your knowledge and the tools you have at your disposal that counts.

What’s been the biggest highlight for Loveshack?

All the accolades have been incredible and we’re so honoured by them, but I personally would have to say that actually just making the game and getting it to market was the biggest achievement. Mainly because of how much work we had to put in the get there. From bootstrapping the company, applying for grants from Screen Australia and Film Victoria, running the business, it’s sometimes amazing there’s even been time to even to make the game itself.

Towards the end of development, around September-November last year, we were all working 18-hour days, seven days a week. It was intense. And while we planned everything and we did our best to mitigate such crazy work hours, it was our collective desire for the game to be the absolutely best it could be that kept us up late; perfecting that last detail in some level art, polishing a piece of foley audio so it sounds just right, getting a section of the user interface to feel just that little bit more intuitive. I guess as a result of all that hard work, our reward will come this weekend when we all set off for San Fran to attend the Independent Games Festival (IGF) awards at the Games Developer Conference (GDC), where we’ve been nominated for ‘Excellence in Design’.

What advice would you give to fanboys looking to become game designers?

My main piece of advice would be to look for inspiration outside of games. If you restrict yourself to finding ideas simply by playing and studying other games, you may end up making copies of them. It never ceases to amaze me, but all of what I consider my best ideas have come when I’ve been watching a film, looking at a painting, reading a book, or just living life. The more you mix your life experiences up, the more likely you will be to take something that isn’t seemingly related to video games at all, plugging that idea into a gameplay idea or some game art, and coming up with something crazy and new.

On a vocational level, education is important, but the best way to learn is just to start making stuff. If you’re seriously interested in getting into the industry, sit down and make a game. It’s the same as picking up a guitar and starting a band. You have to learn to play the guitar of course, but it’ll be the fastest way to learn!

Want to make video games for a living? Get qualified with our range of game design courses.